Walking through the busy city of London with my mother, during summer vacation back in 2011, our day was packed with tourist attractions and visits to stores that haven’t made their way to Germany back then. We walked red lights like the locals and became one with the fast pace of the city.

As we were walking along the Serpentine and on to West Carriage Drive in Hyde Park a large black box caught my eye. To me it was a black box both literally and figuratively. Its few openings on either side, hardly visible with the sun glaring from above, seemingly lead into darkness. They gave me no clue on what would be inside - if there even was an inside to the box. Today, I can’t remember if we got there by chance or if my mother planned on taking me there that day.

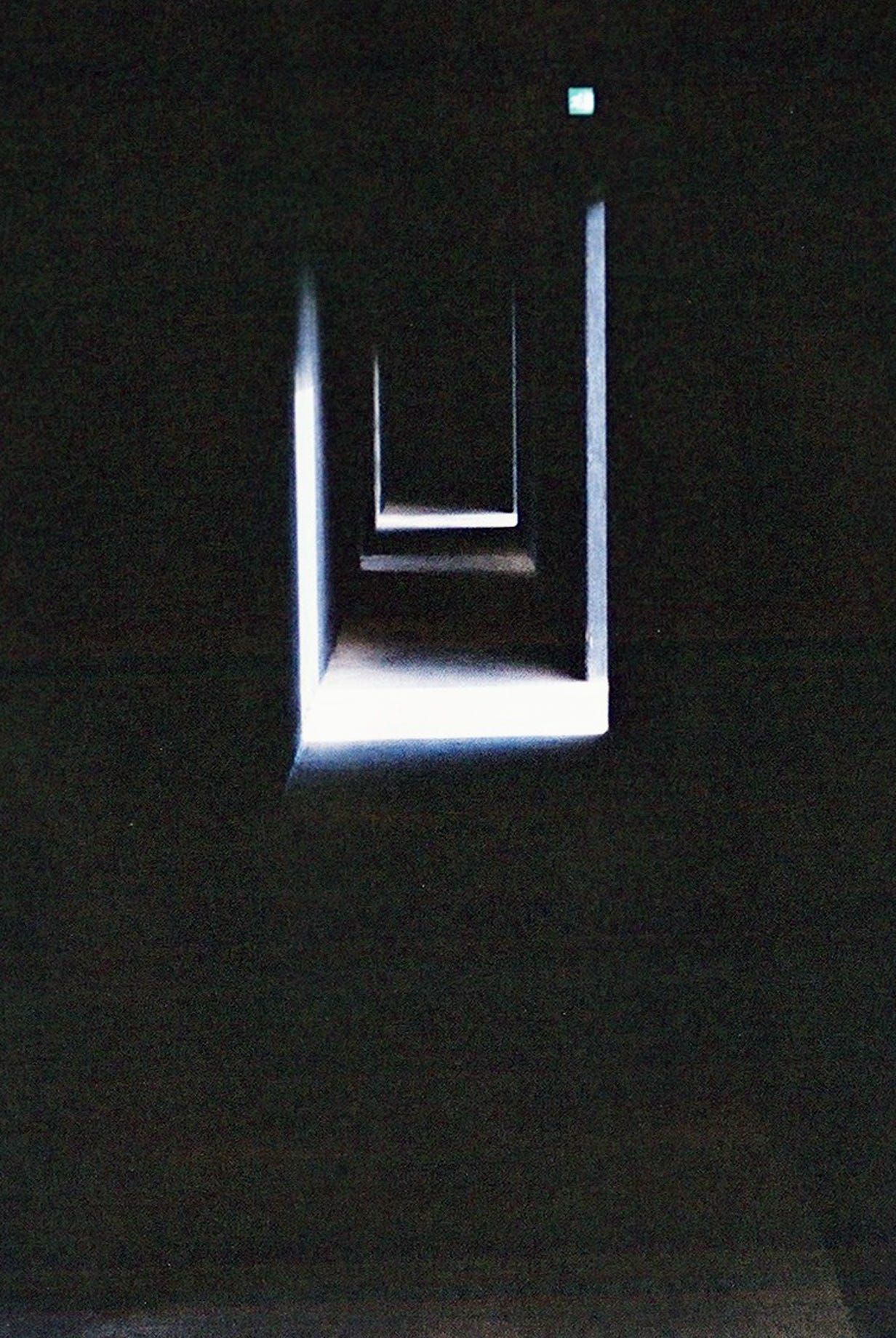

As we approached the box my curiosity rose. I remember stepping into the box, standing still for a moment, giving my eyes some time to adapt to the darkness. Not knowing where to go and what I might come to find I slowly moved forward. After a visit to the London Dungeon not too long before I was on my guard. The dark tunnel did not seem to end with either side fading into darkness in the distance. When my eyes finally adapted to the darkness I could make out rays of light left and right from where I entered. Were these rays of lights just the openings on the other side of the box? Would this turn out to be nothing more than a dark, tunnel-like structure? There must be more to this box, I thought.

I made my way towards one of the illuminated openings on the other side of the tunnel. Stepping through the opening a courtyard, enclosed by black walls, opened up in front of me. With no connection to the outside, except for the sky above, I was completely focused on the center of the courtyard.

An exuberant garden largely occupied the footprint of the courtyard. Flowers, bushes and ferns merged into one thick green mass highlighted with sprinkles of color. An alleyway encompassing the rectangular garden gave it its boundary. Yet it seemed like it was trying to outgrow its assigned perimeter and take over the whole courtyard. The black box, it seemed, merely acted as a shelter for the garden.The garden was here for us. And yet, at the same time, it was here just for its own sake. There was no way to stroll through it or immerse yourself in it. All one could do was take a seat on one of the benches and observe it.

It was only then that I realized that the world around me had fallen silent, sitting next to my mother on one of the benches in the shadow, studying the garden. There was no trace left of the bustling city we had experienced all day. The garden and the sky seemed to be everything that remained. There was no traffic noise, no visual excess and not even conversations from other visitors around us to be overheard. Everyone just sat or wandered in silence. The black box sheltering the garden became a shelter for us as well, keeping out the overwhelming impressions of the city.

After sitting in silence for a while we made our way towards the exit. It seemed like the dark alleyway now braced us for the outside world. Stepping out of the black box it felt like I was returning from a place which seemed like a thousand miles away.

Creating experiences and shaping atmospheres

I later learnt that this black box was the 2011 Serpentine Pavilion designed by renowned architect Peter Zumthor. I also learned that the experience I made when visiting the Pavilion was no accident but the effect of a carefully curated sequence of impressions. Discovering that there was a set intention behind the Pavilion and that it actually made a difference in my perception got me thinking. It made me realize that architecture is not only about churches and skyscrapers but ultimately about experiences and atmospheres. It also made me realize that these experiences and atmospheres embedded in the built environment, even unconsciously, shape our everyday lives.

When Peter Zumthor was asked to design the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion his mind was preoccupied with other projects he was dealing with at that time. Working on gardens and a park he came to think that this Pavilion could tie in with his other projects and accepted the commission. Working together with famed garden-designer Piet Oudolf, Zumthor set out to create a space where visitors would “take the time to relax, to observe and then, perhaps, start to talk again – maybe not.”

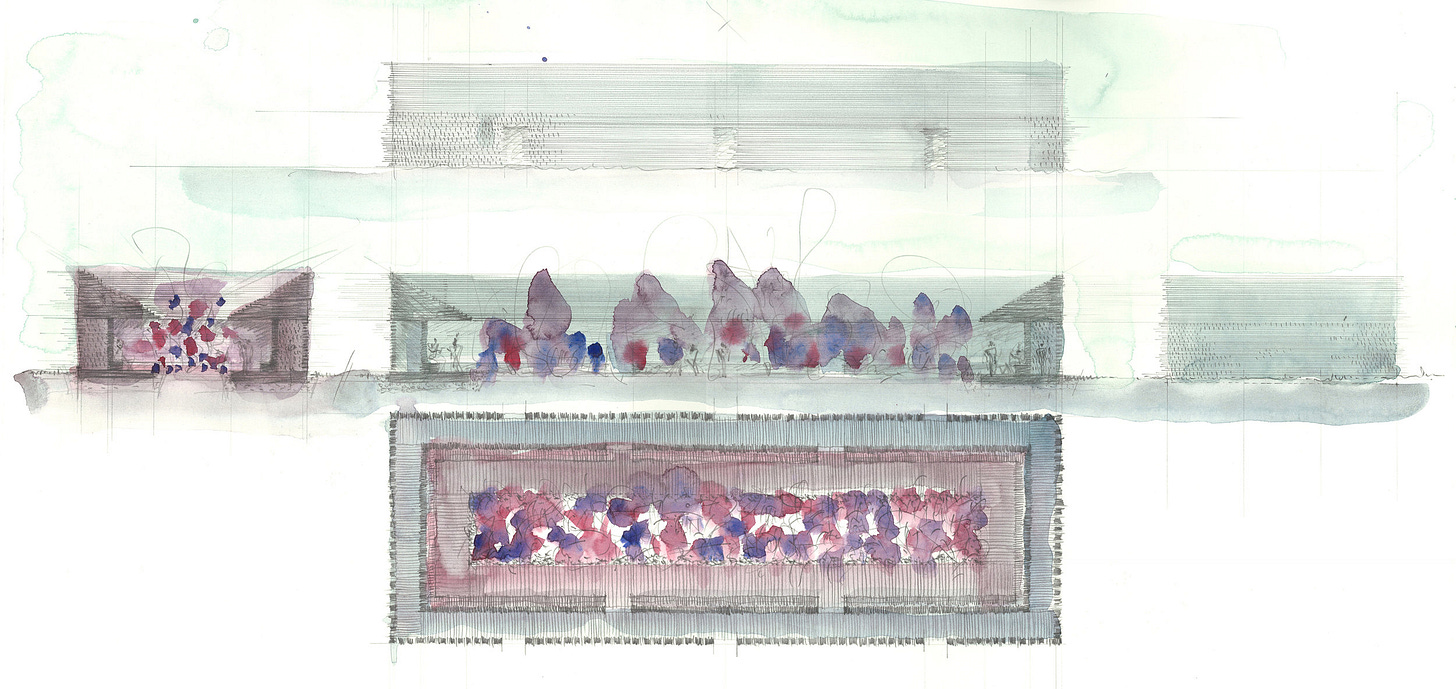

Examining Zumthor’s watercolor of the Pavilion one can identify the key aspects of the design and the intended atmosphere immediately. A black box from the outside, turning into a black mass that you walk through, ending up in a colorful garden with no connection to the outside, except for the sky. What we are left with is a Hortus Conclusus, an enclosed garden separated from its surroundings.

Approaching the pavilion it does not reveal its function to the visitor. Only the ones curious enough to step inside will eventually come to find what the black box is all about. Zumthor had the exterior painted black deliberately to prepare the visitors for the transitional space they find themselves in after entering the Pavilion. Wandering through this transitional space, in nearly complete darkness, visitors are induced to recalibrate their senses and arrive at the garden in the right state of mind. Having passed the transitional space and looking through the inner openings of the black mass all one sees is the garden, the pavilion’s centerpiece. Only by stepping inside, looking left and right the alleyway encompassing the garden becomes visible. Being protected from the elements by the protruding roof and having a place to sit down invites the visitor to stay for longer. The outer and inner openings in the black mass surrounding the garden are placed far apart from each other. There is no way to catch a glimpse of the inside while you are outside. More importantly, once you are inside there is no connection to the outside distracting you from the garden.

From approaching the pavilion, to walking through a black mass and finally sitting down to observe the central garden all of the steps along the way were created to evoke and intensify an emotional and sensuous response. When asked by Julia Peyton-Jones, former director of the Serpentine Gallery, what the recipe for creating an emotional response in his projects is Zumthor’s answer is as simple as it is vague:

“The recipe? I don’t know. I think it starts out with the intention to create emotional space. This is what I want to do. I don’t set out to do a beautiful object that you look at from the outside. I like that too, but it’s not the real core of what I’m aiming for. It’s always the emotional space, but with the correct emotion for that work. I want to make it so my mother, for example, could understand it: if she saw the Pavilion she’d say, ‘Sure. It’s a garden.’ ”

Further reading

A great examination on the aspect of material in Peter Zumthor’s work with a focus on the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion can be found in Susana Ventura’s paper on “Material experimentation in Peter Zumthor’s creative process: research design through material inquiry”.

Great opening of your Substack! I totally agree that architecture is about experiences and atmospheres that shape our everyday lives.